Virgil Hawkins Historical Society Inc

Efforts of the Historical Society near Okahumpka Florida

OUR MAJOR PROJECTS

INTRODUCTION: When Virgil Darnell Hawkins died in February of 1988, the only recognition of his life was the following cracked nameplate for what looked like a pauper’s grave in one of the many minimally-maintained segregated black cemeteries in Florida:

During the three decades since Mr. Hawkins’ death, members of the Virgil Hawkins Historical Society Board have devoted thousands of hours to projects which have sought to honor the sacrifices and efforts of our Civil Rights Legend. Our goal is to insure that (a) Hawkins’ contribution towards making Florida and our nation a more perfect union, will be remembered; and (b) Hawkins life will serve to inspire those who continue the efforts to end discrimination and injustice. The following are examples of those efforts:

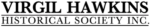

On September 15, 2021, (the anniversary of when the black student began attending classes) UF held a dedication ceremony for this historic marker, which is located at Bryan Hall, the building where the first black student attended law school. The following is a link to the dedication ceremony: UF’s Integration Pioneers Historical Marker (ufl.edu)

Integration Marker at University of Florida

(November 2013 – September 15, 2021

At the request of UF students, Board members of the Hawkins Historical Society waged an almost decade-long campaign to erect a visible recognition of the efforts of Virgil Hawkins and initial black students to desegregate the University of Florida at a prominent location on UF’s main campus. Undeterred by initial rejection, our efforts continued until they succeeded. On September 15, 2021, (the anniversary of when the black student began attending classes) UF held a dedication ceremony for this historic marker, which is located at Bryan Hall, the building where the first black student attended law school.

Hawkins Monument

(February 11, 1991)

The Hawkins monument is located at the beginning of Virgil Hawkins Circle next to the Okahumpka Post Office, a few blocks from the home where Virgil Hawkins grew up. The monument was designed in 1989 and from 1989 – 1991, members of the Board of this Foundation raised funds (including T-shirt sales) for the monument’s construction. It was erected and dedicated in February of 1991,

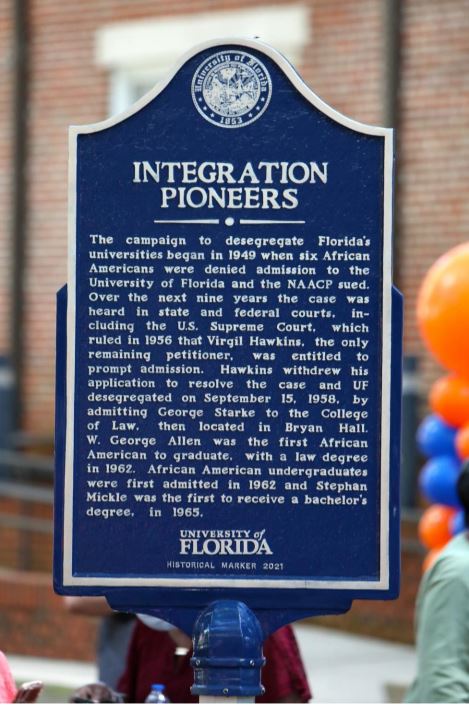

Groveland Four Exoneration and Monument

(2019 – 2021)

One of the events that convinced all of the men and women who sued for admission to UF except Virgil Hawkins to withdraw from their lawsuits was the November 1951 shooting of two of the Groveland Four defendants, by Sheriff Willis McCall while transporting them to a retrial obtained by Thurgood Marshall by Order of the US Supreme Court. Sam Shepard died at the scene. Walter Irvin survived, but McCall was never indicted for Shepard’s murder and was repeated reelected Sheriff through 1972. Board member Beverly Robinson, a relative of Sam Shepard, with the support and assistance of Florida State Representative Geraldine Thompson, led a campaign which initially led to the 2019 pardon of the Groveland Four, the dedication of a monument at the Lake County Courthouse in 2020 and culminated in the November 22, 2021 exoneration of all four by Judicial Order entered at a court hearing at the Lake County Judicial Center.

Okahumpka Rosenwald School Restoration

(Ongoing Project)

A few blocks from the Virgil Hawkins Monument is one of the few remaining Rosenwald Schools, built during the early 20th Century to provide separate but unequal education to black students. A project created by Sears Roebuck co-owner Julius Rosenwald, provided funding grants for the construction of mostly one-room schoolhouses that enabled black students like Virgil Hawkins to obtain an education through 10th grade. Most of the land where the Okahumpka Rosenwald school sits was donated by Virgil Hawkins’ parents, Mr. Hawkins met his wife Ida when she taught students there. The Hawkins Historical Society and members of its Board have been participants in the effort to preserve and restore the Okahumpka Rosenwald School. The dedication of a plaque (photo above with Board members Harriet Livingston and Harley Herman) at the school site was dedicated on November 13, 2021. In January of 2024 the Lake County Commission approved a major grant of $287,310 to commence the restoration of the school Representatives of the University of Florida school of architecture have assisted in the restoration design. The Hawkins Historical Society continues to work with the Okahumpka Community Club to fund the school’s restoration.

Virgil Hawkins Civil Legal Clinic

(1988 – 1989)

In 1988, while his petition to the Florida Supreme Court decision to posthumously reinstate Virgil Hawkins’ Florida Bar membership (to grant his 1983 wish: “When I get to heaven, I want to be a member of the Florida Bar”) was pending, our Founder, Harley Herman requested that the University of Florida College of Law name its civil legal clinic after Virgil Hawkins. The goal of the naming of its third-year law student clinic was to enable students who have obtained the education Hawkins was denied, to represent in his name, the clients Hawkins spent a lifetime seeking to serve as an attorney. When the law school Dean and UF’s President rejected this request, Herman sought out and obtained the sponsorship by State Senator Carrie Meek (who would become one of Florida’s first black Congresswomen) and State Representative Alzo Reddick of a bill to require UF to name the clinic after Virgil Hawkins. Though opposed by UF until Florida’s Governor signed it into law and initially snubbed with a trash can placed under the dedication plaque, later Deans of UF’s College of Law have embraced the efforts of Virgil Hawkins and in the past decade an interactive display of Mr. Hawkins’ history and legacy has become a permanent part of the law school’s library.

Integration Anniversary Events at the University of Florida

(1998, 2008 and 2018)

Until the Integration Historic Marker was erected at the University of Florida in September of 2021, most UF students, faculty and visitors had no knowledge both that UF was once segregated and that it took a decade of lawsuits in the 1950’s for Virgil Hawkins, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund to end the denial of admission of African American students to Florida’s primary taxpayer-funded university. UF’s integration was unique among deep south universities, as it was accomplished without the violence experienced at the Universities of Mississippi and Alabama a half decade later.

In an effort to insure that at least some students and faculty would learn of and disseminate this history, members of the Board of the Hawkins Historical Society have campaigned for, participated in and spoken at events on the UF campus every ten years, to commemorate the 40th (1998), 50th (2008) and 60th (2018 -2019) anniversary of the admission of the first black student to the University of Florida. The 40th anniversary event was highlighted by having Federal Judge Constance Baker Motley (Hawkins last NAACP attorney who secured the 1958 desegregation order) as its keynote speaker. It was one of her last speaking events prior to her passing in 2008. Events in 2008, 2018 and 2019 have preserved this history at the university. Although UF’s President hasn’t participated in these anniversary events since the inaugural event in 1998, it is hoped that his participation at the September 2021 dedication of the Integration Historic Marker will usher in a resumption of the UF’s embrace of this important part of its history.

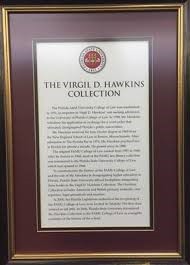

Preservation of the Hawkins Law Books at the FSU Law School

(1999)

One unintended byproduct of Hawkins’ lawsuit to desegregate the University of Florida, was the creation and opening of the FAMU College of Law in 1951. FAMU’s law school was a direct violation of the 1950 US Supreme Court decision in Sweatt v. Painter (339 US 629, 1950), (which ruled that hastily-created separate law school was not equal to Texas’ law school for white students and thus denied Mr. Sweatt’s 14th amendment rights), but was opened so Florida could claim it had afforded Mr. Hawkins a law school in Florida that he could attend. (Florida even sent Hawkins a telegram informing him that an application he never submitted to FAMU had been accepted and directing him to report to FAMU to begin his legal studies.) Despite the illegality of Florida’s creation of the FAMU law school, it purchased a full library for the law school and maintained its operation while the Hawkins lawsuit was pending. As a result, FAMU educated and graduated over 50 law students, many of whom became Florida leaders, including Florida’s first black Secretary of State: Jesse McCrary, Jr. Following the 1958 desegregation Order, Florida embarked on a process of defunding the FAMU College of Law so it could use its funding and law library (but none of its professors) to create a Tallahassee law school at FSU where white lawyers could send their sons and enable them to avoid the stigma of obtaining a law degree from the “College for Negroes”. The FAMU College of Law’s last class graduated in 1968.

Recognizing the historical significance of the law books from FAMU’s law school and the likelihood that after decades of use, these law books would be discarded and replaced, members of the Board of the Hawkins Historical Society began a campaign to obtain FSU’s approval of the preservation of FAMU’s law books. Although they had been “integrated” with books purchased after the FSU College of Law began operations, each was identifiable by the FAMU seal embossed in its initial pages. In contrast to the resistance encountered at the University of Florida, the dean of FSU’s law school agreed to this request and created a special collection of these books which it named: “The Virgil D. Hawkins Collection”. It was not known or anticipated at that time, but as a result of a hard fight led by Attorney Bishop Holifield, the FAMU College of Law was reopened in Orlando in 2003. Upon the opening of its law library, the now-identified and preserved Hawkins Collection has returned to the FAMU College of Law, where today’s students can be inspired by the hands that held these books decades earlier.

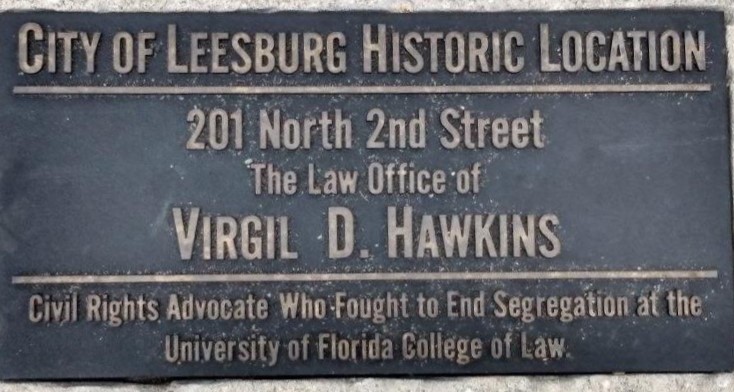

Historic Marker for Hawkins Law Office Site

(June 9, 2022)

When Virgil Hawkins obtained his law license in 1976 at age 70, he opened his office in downtown Leesburg at 200 North Third Street, Leesburg Florida. Despite decades of desegregation, this was a first for Leesburg. Black businesses were located on “the other side of the railroad tracks” in a section of Leesburg known as “The Pine Street District”. During segregation, black residents lived in the area around Pine Street that bordered the citrus packing plant. This enabled them to walk to the plant location and to be bused to the groves and pick oranges for processing. Locating his office in the white business community It was one of the reasons Leesburg’s all-white legal community resented Mr. Hawkins’ attempt to join their profession. Facing scrutiny of his efforts that few lawyers could survive, Hawkins surrendered his law license and closed his office on April 17, 1985. Less than three years later, he suffered a massive stroke which ended his life. While one African-American attorney tried to follow Hawkins’ lead, Leesburg’s legal community remains all white, over three decades later. The marker’s dedication ceremony at which the City of Leesburg closed the street in front of Hawkins’ office, took place on June 9, 2022.

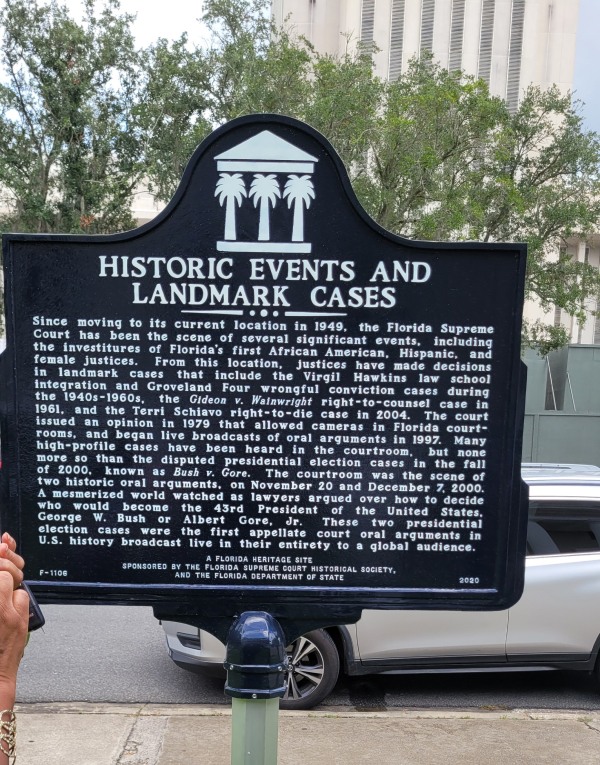

Historic Marker at the Florida Supreme Court

(August 2022)

In 2020 the Florida Supreme Court Historical Society and the Florida Department of State created a historic marker for the history of the Florida Supreme Court. It listed the Hawkins 1950 litigation to desegregate Florida’s universities as one of five significant cases in the Court’s history. Unfortunately, when the Hawkins Historical Society was contacted in 2022, the plaque had never been erected and was in storage in the basement of the Florida Supreme Court. On behalf of our Historical Society, Harley Herman contacted and wrote to numerous officials in Tallahassee and was able to obtain agreement to install what had been a discarded and mothballed commemoration of Florida Supreme Court history. In August of 2022, the marker was installed at the front entrance of the Florida Supreme Court where the Court’s legacy is now on display.

FAMU Law School Marker

(September 9, 2022)

The FAMU College of Law was established in 1951 as a byproduct of Virgil Hawkins lawsuit to obtain admission to the University of Florida College of Law. In an effort by the State of Florida to defy the United States Supreme Court landmark decision in Sweatt v. Painter (which held that the creation of a separate law school for black students was not equal to and thus not a permissible alternative to the admission of Heman Sweatt to the all-white law school at the University of Texas). Despite its creation with the intent to preserve segregation, the FAMU College of Law graduated 57 students from its opening in 1951 until its closure in 1966, when its funds and law library were used to create the law school at formerly all-white Florida State University. By contrast in the decade from when Virgil Hawkins compelled the University of Florida to admit black law students in 1958, only one black law student had graduated from UF. It would take both UF and FSU’s law schools until the mid-1980’s for their graduation of black law students to equal the 57 graduates of the FAMU College of Law. In 2002, after extensive work by attorney Bishop Holifield and FAMU professor Reginald Mitchell, the Florida Legislature reopened the FAMU College of Law at a new campus in Orlando, but the decades-old site of the College of Law at FAMU’s Tallahassee campus had faded into lost history, with its site being merged into a portion of the FAMU library. In 2022 Hawkins Society President, Harley Herman began work with prominent black lawyers and historians in Florida (Marilyn Holifield, H. T. Smith and UF law professor Kenneth Nunn) to obtain authorization for a historic marker to be erected at the former entrance to the Tallahassee FAMU College of Law. In contrast to efforts to recognize Virgil Hawkins at the University of Florida, the FAMU Board of Trustees quickly approved this proposal. On September 9, 2022 the marker listing the names of all 57 graduates was dedicated at the law school entrance.

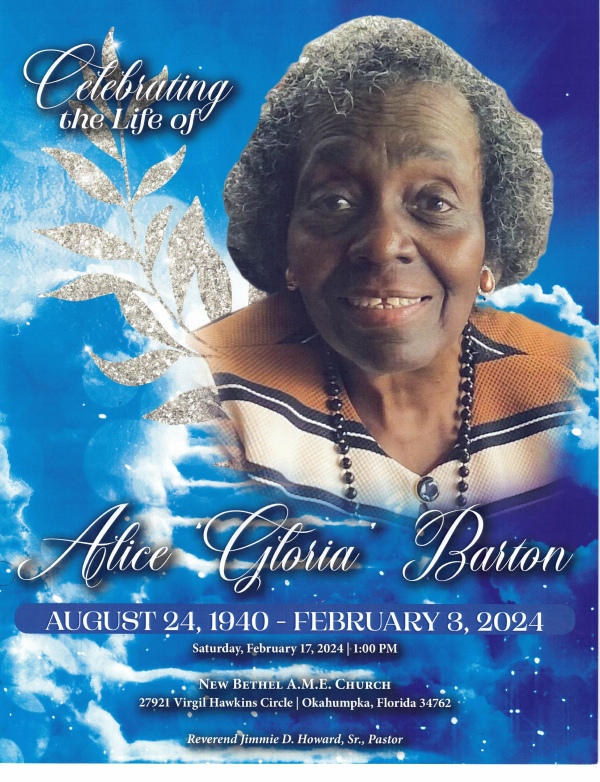

The Passing of Hawkins niece February 3, 2024: Alice Gloria Barton

On February 3, 2024, the Hawkins heritage lost one of the three remaining Hawkins family members who both grew up and lived through the period in the 1950’s when Virgil Hawkins risked both his life and the lives of his family to pursue the lawsuits to desegregate the University of Florida. Know as Gloria, Alice Gloria Barton was directly involved in those efforts, often riding with her aunt, Ida Hawkins when she would drive at night to secretly meet with her husband Virgil, during the decade when it was unsafe for any family member to be publicly associated with Mr. Hawkins. Gloria and her sisters were also present during the incident described in Gilbert King’s book: “Beneath the Ruthless Sun”, when Lake County Sheriff’s Deputies removed their brother Melvin from a church service, so he could be arrested on a pretext, in an effort to intimidate Virgil Hawkins’ efforts to sue for UF’s desegregation. Melvin’s life was only saved after Florida NAACP officer, Robert Saunders obtained the intervention by Governor LeRoy Collins, and secured Melvin’s release from jail. In the early 1960’s, after the lawsuit ended, Gloria drove to New York City with her Aunt Ida, where Virgil Hawkins introduced them to his lawyer: Thurgood Marshall. For decades Gloria and her sister Harriet Livingston were the primary individuals to provide first-hand information about their uncle’s journey from childhood through his efforts at age 70 to capture a sliver of the legal career he would have attained two decades earlier if Florida had complied with the lawful orders of the United States Supreme Court.